When I was a young person, I somehow became fascinated by symphonic music, “classical” music, if you will. Heaven knows how, because I don’t come from a family from whom I would have absorbed that kind of taste. But my father bought a stereo one year, one of those huge pieces of furniture of the early-1960s, all spiffy in its moderne design. (Looking back, I’m sure it was one of those things that he didn’t tell my mother about, sort of like most of my computers, and I’m sure it had the same chilling effect on their relationship.)

He also bought a couple of cheapo hi-fidelity LPs (if you don’t know what an LP is/was, click here), and it was from those that I began my musical journey. It was all what I would call “trash music,” the thrilling cheap stuff that we discount at our soul’s peril: von Suppé overtures, operatic marches, that kind of thing. But it was enough. I was hooked.

I think the turning point came one day when my father and I were in a record store, and I had picked up both Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Walter Carlos’ Well-Tempered Synthesizer. (He’s Wendy Carlos now, but let that pass.)

I was told I could only get one of the two. After much deliberation, I chose the Carlos album, and I believe that has made all the difference.

Fast-forward a couple of years, when I was in high school and had returned from GHP, my brain enflamed and open for more. I went to the public library, a Carnegie library on the corner of the court square, and asked for The Lord of the Rings. They didn’t have it, but they ordered it. They also had, which I had never noticed before, albums to check out. It was an odd, eclectic little collection, but it was choice: Oistrakh & Stern in Vivaldi double violin concerti; Landowska (I think), Bach’s 12 Little Preludes on a massive harpsichord; Ormandy and the Philadelphia in Shostakovich’s 4th and 5th, which started me on my lifelong love affair with Shostakovich. (I remember when his last symphony, the 15th, premiered in the USSR, and waiting breathlessly for it to be recorded by the Philadephia.)

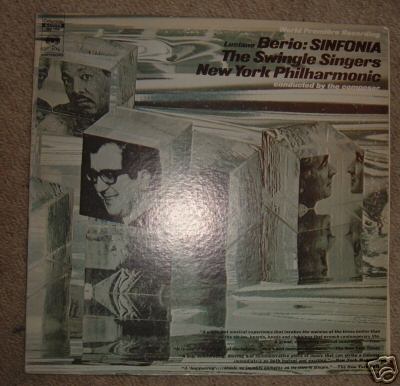

But there was another album which began another lifelong love affair. Its cover was cool, elegant, mysterious, with a mylar surface rippling around lucite cubes, images alternating back and front of the cubes. The liner notes promised a “white-hot” cultural experience.

This is the album:

Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia. New York Philharmonic and the Swingle Singers. The first movement is standard mid-20th century blips and blops, but compelling nonetheless in its use of sound and text. The second movement, “O King,” is a threnody to Martin Luther King, the text made up of the syllables of the great man’s name. The fourth movement sort of a mishmash of what has gone before.

It’s the third movement, “In ruhig fließender Bewegung,” that grabbed my attention and has had such an impact on my life. It started with what was apparently a movement from a symphony by a composer named Gustav Mahler, a symphony called “Resurrection,” his second. This whirling scherzo was merely the vehicle, a transport, for a huge cargo of Western music and 20th century civilization. Phrases from Samuel Beckett floated in and out of focus. Snatches of melodies, passages from great works, zoomed past. Huge blocks of sound, columns of every instrument playing every tone in the scale, threw themselves in the path. But the onward swirl of the Mahler could not be stopped. Berio himself described it as a river which flows “through a constantly changing landscape, sometimes going underground and emerging in another, altogether different place, sometimes disappearing completely, present either as a fully recognizable form or as small details lost in the surrounding host of musical presences.”

What a phantasmagoria! It demanded my attention. I was already well-versed enough in music to recognize many of the allusions, and the Beckett… well, it’s Beckett:

“Well, well, so there is an audience… It’s a free show, you take your seat and wait for the show to begin. Or perhaps it’s compulsory, a compulsory show!”

“Keep going, going on, call that going, call that on?”

“And the spectators, where are they? You never noticed, in the anguish of waiting, you never noticed you were waiting alone.”

“They think I am alive, and not in the womb, either.”

“You try and be reasonable.”

“They don’t know who they are either.”

And then, near the end, the crux of it all:

“And when they ask, why all this? it is not easy to find an answer, for when we find ourselves, face to face, now, here, and they remind us that all this can’t stop the wars, can’t make the old younger, or lower the price of bread, can’t ease solitude or dull the tread outside the door, we can only nod, yes, it’s true, but no need to remind, to point, for all is with us always, except perhaps at certain moments here among these rows of balconies, in a crowd or out of it, perhaps waiting to enter, watching. And tomorrow we’ll read that Beethoven’s 4th Piano Concerto made tulips grow in my garden and altered the flow of ocean currents. We must believe it’s true.”

We must believe it’s true. Despite the bleakness of life, “there must be something else, otherwise it would be quite hopeless; but it is quite hopeless” , we must believe that all this, the art which comes from god knows where, the thing we make that was not, all this will come to us with its own “hope for a second of resurrection or almost.” We must believe it’s true.

This extraordinary piece of music has been a major part of my psyche for more than thirty years now. I currently own three different performances: Chailly/Concertgebouw; Eötvös/Göteborgs Symphoniker; and Boulez/Orchestre National de France. I wish I could say I still owned the Berio/NYPhil, but I put the LP on reserve at the VSU library many summers ago (I’ve forgotten why) and forgot to retrieve it. It’s now part of their permanent collection, and of course my name is nowhere on it. I owned it on CD but loaned that to someone in my past, and now it’s out of print and unavailable as well. I like the Boulez the best among the three I have for the control of the orchestra and for the clarity of the key portions of the text.

Through Sinfonia, I discovered Mahler, and that alone has got to count as a major addition to one’s life. We must believe it’s true.

http://www.avantgardeproject.org/agp83/index.htm