We’re working our way through the advice given in The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published, and today we get to answer the question, “Why me?” In other words, why am I the person to write this book?

As I said in the Introduction, I’ve been a creative person my entire life, and my entire adult life has been spent giving others permission to be creative people themselves. Sometimes I taught the knowledge, skills, and attitudes directly; other times I’ve provided the framework for that to happen.

For example, one of my favorite memories at Newnan Community Theatre Company was our 1995 production of The Winter’s Tale. Our Hermione was a professional actress from Atlanta, Equity even, whose personal goal of playing all of Shakespeare’s queens overrode her concerns about union rules. (She did perform under an assumed name.) She was amazing to work with and had a great time with us. [1]

At the cast party after our last performance, I was looking at my large cast running around enjoying themselves, congratulating themselves on a job well done, and Jen walked up and said fondly, “They don’t know they’re not supposed to be able to do this, do they?”

“No, they do not,” I replied. And they didn’t. They had no clue that tackling one of Shakespeare’s late romances was out of their league. But I had provided the opportunity, and not knowing any better they jumped into the deep end without a second thought. And they did it!

So my commitment to the creative process is absolute, and I’ve developed lots of mad skilz in encouraging it in others.

EGGYBP also asks whether I have anything to say that’s new and different about the topic. I believe I do. Lichtenbergianism (as I state clearly in Chapter One) is nothing ground-breaking; the creative process is the creative process, after all. What’s new and different about the book is the whimsical attitude of the Lichtenbergian Society towards productivity. There are some hardcore ideas in the Nine Precepts, but essentially it’s a way for the reader to stop worrying about getting it done and to step back and see the larger picture. There are strategies for getting started, there are strategies for TASK AVOIDANCE, there are strategies for stopping—but over all, it’s all about permission.

Give yourself permission to create.

—————

[1] I have two other favorite stories from that production. Three—I have three more favorite stories. Story #1: One reason I chose the play was its very unfamiliarity to audiences. How would they take a sprawling play that they didn’t know anything about? In the final scene, Hermione (who died in Act I) ‘s lady-in-waiting Paulina is showing King Leontes a statue of his dead queen. She claims to be able to make the statue move, if he will pardon her use of magic. Every night, when Paulina charged the statue to speak, Jen would do this amazing “come to life” bit, shivering up from her diaphragm as the statue appears to take a breath for the first time. Every night I would watch the audience, and every night they were visibly shocked. It was great.

Story #2: This was the first Shakespeare we did in full Elizabethan drag—and what a show to choose to do that on! The play spans 16 years, covering two completely different fashion periods, and ranges from royalty down to peasants. We went full out, ruffs and corsets and bum rolls and satin and brocade and everything. A week or so before we opened, Becky Clark (goddess) came down from the second floor, where we had chained actors to sewing machines and ironing boards. She was distraught. We weren’t going to be able to finish the 60+ costumes before opening. At that very moment, Act I began onstage: Leontes and his court swept on, everyone wearing as much of their costumes as they had available. Becky was electrified. “That is so beautiful! Yes, we can do this!” and went back upstairs to whip the actors harder. (Corollary story: about a week later, we were running the show and I was out in the seats taking notes. It was Act V, and on came Jennifer Sodko as some lord or other, and I realized with a shock that I had done something I had sworn never to do: create a complete and complex costume for a character who is seen once for less than a minute.)

Story #3: The show is long, very long, and late one night in the middle of Act IV, I heard a huge roar erupt from the bar next door. I think it is a testament to the quality of the performance that none of the audience even tried to get out to go next door to celebrate the Braves winning the World Series. (The cast, who had been following backstage, announced the win during curtain call.)

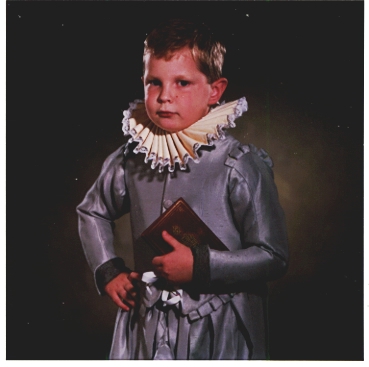

Story #4: All right, I have four more favorite stories. My son Grayson played Prince Mamillius. He was seven at the time, and I needed a Mamillius who could read and whose television privileges I could threaten. My mother volunteered to sew his costume, but she balked at putting on the codpiece—so that night at dress rehearsal I’m safety-pinning a codpiece onto my child when he objects. “What is this?” I explained it was called a codpiece. “What’s it for?” I explained its origins as a “safety valve” from tight leggings in the late Middle Ages, but that at this time period it was merely decorative. “Do the other actors who are male have one too?” (That is literally what he said.) Yes, I said, they all do. He considered for a moment, then announced, “I can use this in my scene: ‘No, my lord, I’ll fight!’” and waved his little codpiece about. I proposed that that might be funnier to spring on his fellow cast members backstage rather than as a bit of onstage business.

Story #4: All right, I have four more favorite stories. My son Grayson played Prince Mamillius. He was seven at the time, and I needed a Mamillius who could read and whose television privileges I could threaten. My mother volunteered to sew his costume, but she balked at putting on the codpiece—so that night at dress rehearsal I’m safety-pinning a codpiece onto my child when he objects. “What is this?” I explained it was called a codpiece. “What’s it for?” I explained its origins as a “safety valve” from tight leggings in the late Middle Ages, but that at this time period it was merely decorative. “Do the other actors who are male have one too?” (That is literally what he said.) Yes, I said, they all do. He considered for a moment, then announced, “I can use this in my scene: ‘No, my lord, I’ll fight!’” and waved his little codpiece about. I proposed that that might be funnier to spring on his fellow cast members backstage rather than as a bit of onstage business.