The included day trip on Day 6 was a walking tour of Regensburg, where we were docked. We anted up for the bus trip to Munich, which was an all-day trip. Our Charming Child had studied in Munich ten years ago, so naturally we had to go see him for Thanksgiving. We kind of wanted to go to there again.

First, oddly, we had to clamber down a bank to get to the bus:

We had been told that the docking situation in Regensburg was precarious—river tourism is up like eleventy-billion percent, and berths are hard to come by—but this was very silly. Technically you would walk down the pathway along the bank until it intersected the road, then walk back (and it just occurred to me that perhaps the bus could have been parked there?), but where’s the fun in that?

The uncertainty of where we would be docking would explain the one real complaint any of us had about the cruise, and that was that we would like to have known ahead of time when the ship would be leaving each day/night so that we could call a cab and run into town to see an opera or something. (We had thought about getting tickets to a ballet in Budapest ahead of time, but thank goodness we didn’t: we sailed before curtain.) By this time I had figured out that a lot of the next day’s schedule had to be figured out at the last minute based on exigencies of each port, and the Regensburg situation confirmed it. In fact, the ship changed places twice that day while we were away.

Munich was several hours away, and our tour guide was able to give us the standard history of the Autobahn. It seems the Germans invented the idea of the interstate way back in the 1920s, but had barely gotten started on it when Hitler came to power. He promised jobs for hundreds of thousands of people to build this system of highways, but a) employed far fewer than that; b) started WWII, which put a dent in their progress. Eisenhower picked up on the idea, though, and the first bit of our interstate system was laid down outside Tifton, GA, in the early 60s.

Most of what we drove through was farmland, and here were the two major crops:

The poles/wires area is hops, which is essential to the manufacture of beer. There were huge tracts of land given over to this crop, and most of it was bespoke, already sold to major breweries both in Germany and around the world, Bavarian hops being in demand.

The other crop in the bright yellow field in the distance is canola. We had seen it in abundance flying into Budapest, and every landscape we drove through had tons of it. It’s used for biofuel mostly.

Munich is a lovely city, but it and many cities on our tour share the same trait. (I’ve already blogged about this over at Lichtenbergianism.com, so apologies if you’ve already read it.)

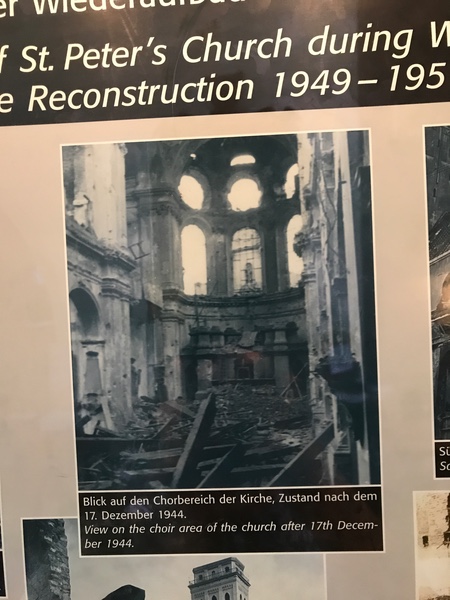

Here is the interior of St. Peter’s Church:

Pretty standard 18th-century Baroque, right?

It’s not. It used to be, but what you see here is less than 100 years old.

In Munich, in Nüremburg, in Dresden, in Vienna: large parts of the cities were destroyed during the war, some almost completely. And they were rebuilt as they were before, especially the large public buildings like churches. All those glorious Baroque interiors are complete reconstructions.

It is very hard for us Americans to understand this, but the devastation of the war is still part of the fabric of European society. Our tour guide in Passau was emphatic in her memories of CARE packages and of the Marshall Plan and how gobsmacked the Germans were that they were included in those programs. The tour guides in Austria and Bavaria never failed to mention their relief and gratitude that they were occupied by American or British troops and not Soviet. And everywhere, especially in Munich, carefully reconstructed boulevards and façades rose again.

After we got off the bus, we were led through the Old Town to the Marienplatz, the city’s main square since 1158. The main attraction there is the Neues Rathaus, the New Town Hall:

Despite its über-Gothic appearance, it was built in the 19th century. And before you make haha jokes about Rat Houses, Rat is German for advice or counsel.

We were there for the main event: noon. I don’t have a good photo of the clockworks, so I’ll steal one from Wikipedia:

After the carillon chimes noon, the upper figures spring to life, reenacting the celebrations attendant upon a 16th century wedding of one of the Dukes. After that display ends (including a joust), the lower level cranks up with a depiction of the Schäfflertanz, a dance performed every seven years as part of the whole Black Death thing. It was charming and fun.

The Rathaus is built around a courtyard:

There is al fresco dining:

This area was covered by stalls the last time we were here; the Christkindlmarkt was opening the day we left.

Have you seen it yet? I did, ten years ago, and was a little bummed that now there were tables and chairs out there.

Here, have a close-up:

That’s right, there’s a Chartres-style labyrinth in the cobblestones of the courtyard. It’s part of the original design, but is oddly unmentioned in any guide to the place. (Neither is it in the World-Wide Labyrinth Locator.)

We were taken to lunch in the Ratskeller, which is also original to the building. The vaults are painted with witty banners about drinking.

I forget what I had for lunch, but for dessert of course I had apfelstrudel.

It has all four major food groups: pastry, ice cream, vanilla sauce, and whipped cream.

And now I must tell you an are-you-kidding-me story of the Newnan Vortex™.

With us on the Munich jaunt were a trio: a couple from Wisconsin, and her sister from Scotland. (The wife was originally from Scotland.)

Oh, we said, one of Newnan’s sister cities is Ayr, and we went there in 2013 with a squad of children to sing with the Scottish National Opera’s Tale o’ Tam. This was a piece commissioned by Ayrshire the year before, based on Bobby Burns’ “Tam O’Shanter” and involving two adult opera singers, a small pit orchestra, and as many children as you can cram onstage. Ayr decided to repeat the show and invite students from its sister cities in the U.S., Norway, and Germany.

I was tasked with auditioning, training, and chaperoning these students on an all-expenses-paid trip to Scotland. What’s not to like?

Ah, said Hilary, the sister. I remember that. It was quite an undertaking. The man I work next to was involved in it. Do you know John Wilson?

That’s when I smacked my lovely first wife, who was focused on the next table. John Wilson was a tall, handsome Scot with argyle socks whom some of our party found quite charming, and indeed he was in charge of the whole Tale o’ Tam project.

Do you by any chance know Mai Lawrence? we asked Hilary. Mai was one of the Scottish teachers with whom we bonded, and with whom we exchange Christmas cards—until Mai retired, moved, and never put her return address on her cards.

I taught with Mai, Hilary said. I’ll track down her address through a mutual friend on Facebook and email it to you.

Well there you go.

Those of us who live in the Newnan Vortex™ should be used to this kind of thing, but it’s always a bit unnerving when it happens. And it always happens.

On the ride back to the ship, there was the inevitable giggle about gagging:

(Ironically, Bad Gögging does have a labyrinth in the Labyrinth Locator.)

And the morning and the evening were another day.

no moar large organz?

Hang in there, Jobi-Wan. Prague is coming.