Last stop: Nuremberg.

But first it was a trip to the Faber-Castell factory you guys!

That’s right, we signed up — and paid extra — to tour an office supply plant. Apparently this is a niche interest, since it was only the four of us plus two ladies who had shipboard credit they needed to spend on the tour. (For the record, they did not regret their choice.)

Faber-Castell started in Stein in 1761, and there it still is. It makes 2 BILLION pencils a year, worldwide.

Stein, right next door to Nuremberg (they really don’t like it if you say “outside of Nuremberg”), is a pretty little town, although we didn’t get to see much of it.

This is a row of former fishermen’s houses, renovated and used for low-income housing.

A view of the original F-B factory:

Looking more closely, you can see the turbine they still use to generate power from the river, and the windows painted bright colors. These colors actually indicate which department is on that floor; they are not just delicious reminders of the colored pencils you guys!

In the basement is a museum/exhibit explaining both the history of the pencil (squee!!!) and of the company itself. They’ve used a bunch of the old equipment they had lying around, and you can thank me in the comments for not showing every single picture I took of every single item.

Here’s a shelf with samples of graphite, originally mined in England and then in Siberia:

And a close-up:

As I mentioned, all the equipment is the older non-automated stuff, so it’s redolent with graphite and oil:

This is the machine which would take the sludge made of graphite and clay (a mixture devised by Lothar Faber in the 19th century that revolutionized pencil manufacture, allowing for the different grades of hardness) and squeeze it through steel plates to form the leads.

It would come out still wet and pliable; it had to be fired to achieve rigidity.

This Lothar Faber was amazing: he ramped up production; provided housing/education/health/daycare for his workers (establishing the first kindergarten); and realized that if you wanted people to pay more for your superior, green-coated pencils, you packaged them to look special. It still works: I cannot walk by a Faber-Castell display without a Pavlovian response to buy it.

The exhibit was an office supply junkie’s wet dream, with piles of leads and slabs of graphite and bundles of product strewn about with abandon.

Then we went back across the bridge to the current production facility.

On the way, the wording on this sign finally sunk in:

Sommer in der City? Especially when the very next line uses Stadt? (Full translation: Summer in the City / the Nuremburg City Beach / Now it’s getting hot!)

We noticed ten years ago in Munich that English was used like pepper, to spice up your marketing, and our tour guide Fiona (Scottish herself) confirmed that English was still “cool.” It was sometimes barely noticeable in Austria or Germany — at least to those of us with a smattering of German — but in the Czech Republic, where the letters don’t cohere into what you and I would call “words,” the effect was sometimes jarring.

Anyway, back across the bridge, we prepared to enter Faber-Castell’s factory.

You are entirely not wrong if you are thinking MY GOD IT’S WILLY WONKA’S FACTORY!

Just sayin’.

I have no photos, because industrial spying etc, but the process of making one of those gorgeous colored pencils you guys is amazing. Step after step, innovation after innovation—it was incredible. You haven’t lived until you’ve seen a machine round off the top of a pencil, then dip a whole squad of them into paint just to get that colored tip.

Fun fact: Europeans expect their pencils to be sharpened. Americans like theirs not sharpened. (I’m with the Europeans on this one.)

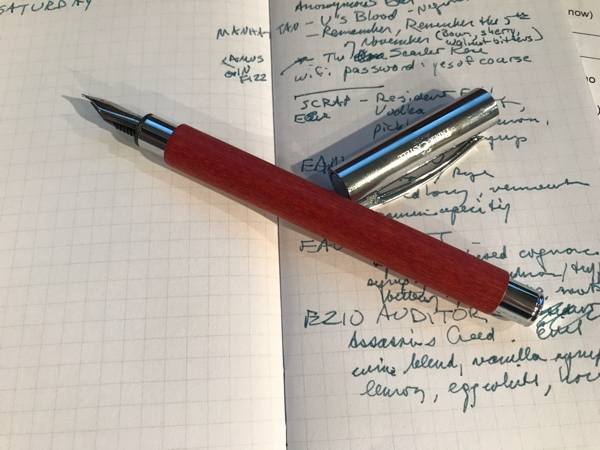

Here’s the second of my three are-you-kidding-me stories: I own a Faber-Castell fountain pen, and in fact it’s my favorite: a not inexpensive rosewood-barrelled finepoint. However, it had developed a habit of leaking for no discernible reason, and the cap had problems staying on, a dangerous combination. I had joked about getting someone to take a look at it from the moment we signed up for the tour but lowered any secret hopes I had when I saw that we were actually going to a pencil factory.

Then at the end of the tour we got a little brand enhancement with a look at some of their premium fountain pens and a shipping room, and then, almost casually, our tour guide pointed out the room on the other side of the hall: “This is our repair facility.”

My gang made little simian hooting noises, my eyebrows flew up, and I whipped out the pen.

“Perhaps they can help me with this—it leaks and the cap won’t stay on,” I said. The tour guide rapped on the large plate glass window, and a young man came to the door. I showed him the pen, he took it, removed the cap, noted its looseness and tutted at the ink stains on the rosewood barrel.

“This is not good,” he said, and vanished.

In 120 seconds he returned and handed me a completely new pen.

Well. There is customer service, and then there’s customer service. That’s one way to conclude a tour.

Of course, this meant we would have to go to the gift shop, because now I needed ink. (As if we weren’t going there anyway.) Many purchases were made. Many purchases were, regretfully, not made.

Back to the ship, where I noticed growing on the banks:

Cardoon! It’s the original, not the hybrid taking over my side yard, because every dentata on every leaf has a very sharp spine sticking out of it. Whoever first decided that this thing was edible was a brave human indeed.

After lunch, to Nuremberg.

We had deliberately not signed up for any of the WWII tours, because one visit to Dachau ten years ago is enough to make the point, but in Nuremberg you cannot escape it.

For example, on our way to the Altstadt, we were driven to and into the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, which I actually did not know existed.

Again, stolen from Wikipedia:

It’s huge. However, it is radically unfinished. We drove into the interior, and such was my shock at the ambition, the scale, that I took no photos. Again, stolen from Wikipedia:

As big as this is, it was going to be bigger: half again as tall, and domed. Like any dangerous megalomaniac, the man loved large adoring crowds, he said letting that hang there for a while.

We also drove through the zeppelin landing fields and the parade grounds:

And then, mercifully, it was on to the Altstadt, where, actually, it was just as depressing.

The Old Town, still enclosed in walls and gates, was completely obliterated by the Allies. It was a deliberate psyops gambit: Nuremberg was Hitler’s “most German city,” and the Altstadt was its symbol. So we wiped it out.

The castle/fortress, never successfully attacked:

The old square:

The little spire in the foreground is a memorial to the Black Plague, recently restored. Almost every place we went had one of these. If you’ve never read A Distant Mirror, by Barbara Tuchman, give it a whirl: the impact of the plague on western culture cannot be over-emphasized.

A little shopping, a little strolling…

One funny story: as we did the walking tour down from the castle to the square, I noticed a little shop with locally distilled gin. I made a note, and after we were released for free time, I waited patiently while we shopped for Christmas ornaments and basically nonexistent traditional Bavarian shirts for our boy-children. Finally, it was getting close to time to get back to the bus, so I announced that it was time to go check out the gin. I set out, down the hill to the square, and then back up the other hill towards the castle. I forged on; I was not to be deterred by dawdling. I dodged tourists, locals, vehicles. I churned up those cobblestone streets.

I arrived at the shop precisely at the moment the proprietor turned the key in the lock. It was 5:00.

Fortunately, she saw me and saw the look on my face. She opened back up, I apologized for detaining her, and told her I wanted to buy the gin, if I could have a quick sample. (They had sample station set up near the window, hence my bold request.)

The sample was perfection—whether it was enhanced by my vigorous exercise is still to be determined—and I bought a bottle of Ayrer’s small batch malt gin. You’ll meet it again in my “swag” post.

The others finally trailed up as I was signing my receipt.

Back to the bus, back to the ship, for our final night on the ship. That’s right: this was the end of the cruise. We had a farewell toast with the captain/crew, and a farewell dinner, and then we went almost straight to bed: our bags had to be outside our door at 6:15 am. (They give you a chart of luggage/departure times—very organized.)

Here are our hotel manager (whose name escapes me), our Ukrainian captain, and the adorable Soren:

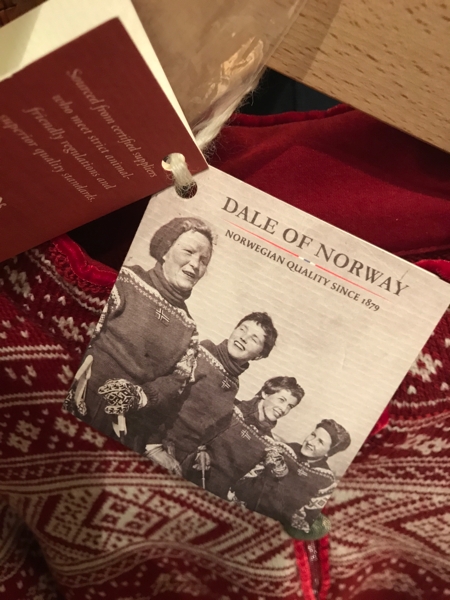

One final joke: the tiny shop area onboard offered Norwegian sweaters, which we didn’t really notice until it was promoted in our final little daily newspaper, and the brand caught my eye:

The joke is that in Aug/Sep of 1975, just before my senior year at UGA, I was the prop master of a production of Godspell that UGA sent to Bergen, Norway, for a three-week stay. One weekend we were taken up to meet Norway’s national playwright at his mountain home, and the train stopped at a little village: Dale. I took a photo, but that was hundreds of years ago and I have no idea where it disappeared. Anyway, “Dah-lay of Nor-vay” became my nickname for a while, and that is how my lovely first wife first knew me.

Note: we’re not done here. Next stop is Prague!