Today is the anniversary of the premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 15, Op. 141, in 1972.

Two years previously, I had returned from Governor’s Honors hungry for more: more art, more theatre, more music, more literature. In Newnan at the time, the most immediate source of a lot of what I wanted was to be found at the Carnegie Library downtown. I’m sure the librarians there were thrilled to see a young patron digging into the more refined corners of the collection with such hunger and avidity; I know as a librarian I would have been.

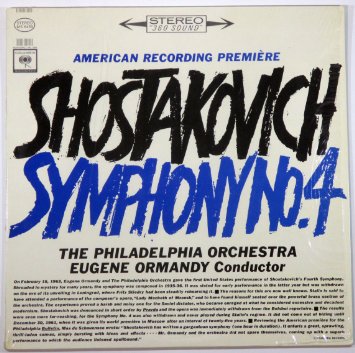

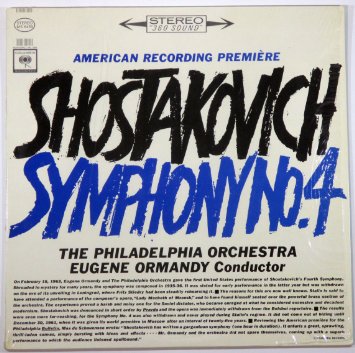

The Carnegie had a small, weirdly eclectic record collection of classical music—about which I’ve written before—and one of the records I discovered was Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4, a work which puzzles many critics but which I found to be a complete planet of musical ideas. Since I was simultaneously reading The Lord of the Rings for the first time, the symphony became cinematically linked to the landscapes of Middle-Earth in my mind.[1]

The Carnegie had a small, weirdly eclectic record collection of classical music—about which I’ve written before—and one of the records I discovered was Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4, a work which puzzles many critics but which I found to be a complete planet of musical ideas. Since I was simultaneously reading The Lord of the Rings for the first time, the symphony became cinematically linked to the landscapes of Middle-Earth in my mind.[1]

You know how it is when you’re young: like a freshly hatched duckling you imprint on your first experiences, so that Eugene Ormandy’s interpretation of that work remains for me the standard against which all others must be matched. I moved on to the composer’s 5th Symphony, his most famous, and then I started collecting the man’s works on my own. He remains one of my favorites.

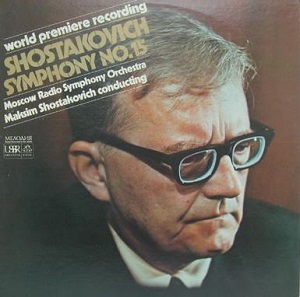

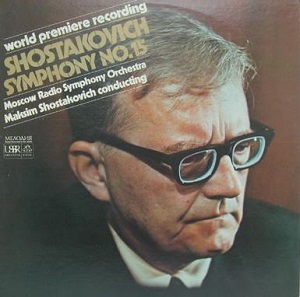

So you can imagine my excitement when it was reported in my senior year in high school—how? How did I learn things like this back before the internet?—that he had written a fifteenth symphony, that it had been premiered in Moscow, conducted by the composer’s son Maksim, and that it had been recorded! I began a waiting game until it was released here in the U.S.

By the time the recording came out, I was at the University of Georgia in my freshman year. There was a record store on North Lumpkin St., and I checked it religiously until one day, there it was. I wrote my check—I’m telling you, I’m old—and scurried back to the dorm.

By the time the recording came out, I was at the University of Georgia in my freshman year. There was a record store on North Lumpkin St., and I checked it religiously until one day, there it was. I wrote my check—I’m telling you, I’m old—and scurried back to the dorm.

Back in the day, O my younglings, music came in these sizable cardboard sleeves with enough room on the back for a great deal of information. The basis of my knowledge of music history comes largely from those liner notes, as we ancient ones called them. The liner notes of Shostakovich’s Fifteenth seemed to indicate that the piece was a great puzzle to listeners and to critics. What was the deal with the William Tell quote in the first movement? The liner notes couldn’t pin that one down, almost suggesting that it was tacky (as did other critics at the time). And then the quote from “Siegfried’s Funeral March” from Götterdämmerung in the final movement—was he resigned to his “fate”?

This inability to pin down the “meaning” of Shostakovich’s intent was in turn puzzling to me. It’s like the reputation of the Fifth, with its final movement of triumphant joy. At least, “triumphant joy” was the phrase used to describe that last movement, but from my very first encounter with the piece I found that hard t0 believe. That was not joyful music; it was angry, furious, destructive music. Why did anyone believe it was “joyful”?

In 1979, after Shostakovich’s death in 1975, Testimony was published. It purported to be a book-length interview with Solomon Volkov and was immediately assailed by the Soviet authorities as bogus; the jury is still out as to its authenticity and there are strong arguments on either side. Nevertheless, in it the composer says:

I discovered to my astonishment that the man who considers himself its greatest interpreter [the conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky] does not understand my music. He says that I wanted to write exultant finales for my Fifth and Seventh Symphonies but I couldn’t manage it. It never occurred to this man that I never thought about any exultant finales, for what exultation could there be? I think that it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat, as in Boris Godunov. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, “Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,” and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, “Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.”

What kind of apotheosis is that? You have to be a complete oaf not to hear that.[2]

Precisely.

Shostakovich’s relationship with the authorities—Stalin in particular—was always precarious. His Fourth Symphony, my favorite, was pulled from rehearsal shortly before its premiere in 1936 after Stalin was offended by the composer’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mzensk . An editorial entitled “Muddle Instead of Music” appeared in the papers, condemning such modernist garbage. The opera company closed the production and Shostakovich pulled his new symphony, which did not have its premiere until 1962. His Fifth Symphony is subtitled “A Soviet Artist’s Reply to Just Criticism.” He kept his bags packed by the front door in case the secret police showed up to disappear him into the gulag; it had happened to others.

So with my first listening to Shostakovich’s new symphony, I heard him saying things that were pretty clear. The William Tell quote? The famous rhythm, of two sixteenths and an eighth, is also Shostakovich’s signature rhythm. He relies on it constantly. The triteness of the quote? Shostakovich’s assessment of his own output: “This is what I have produced because of the regime under which I have struggled. Screw you guys.” (The opening theme of the first movement is the same rhythm and indeed the same intervals as the Rossini.)

The other movements are shot through with references to his past compositions, culminating with that Wagner “fate” motif in the last movement. There the massive passacaglia harks back to his Seventh Symphony (almost an inverted version of it, in fact), and the whole thing ends as the structure evaporates into fragmentary quotes of the symphony’s main themes, the percussion toys ratcheting out a clockwork reminder of his Fourth, his grandest failed experiment, the path not taken because he was forced from it.

Dmitri Shostakovich was a deeply unhappy, depressed, and grim man—and who can blame him? He survived when others didn’t, and he kept his artistic integrity even while knuckling under to the despotic regimes of the USSR. As his life came to a close—he had cancer as well as heart problems—he limned his misery in his final large work.

I raise my glass to him.

—————

[1] It is a tribute to Howard Shore’s genius that his score for the movies surpassed that linkage in my mind. As if Howard Shore’s genius needs a tribute from me.

[2] Shostakovich, D. D., & Volkov, S. (1979). Testimony: The memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. New York: Harper & Row.

The Carnegie had a small, weirdly eclectic record collection of classical music—about which I’ve written

The Carnegie had a small, weirdly eclectic record collection of classical music—about which I’ve written  By the time the recording came out, I was at the University of Georgia in my freshman year. There was a record store on North Lumpkin St., and I checked it religiously until one day, there it was. I wrote my check—I’m telling you, I’m old—and scurried back to the dorm.

By the time the recording came out, I was at the University of Georgia in my freshman year. There was a record store on North Lumpkin St., and I checked it religiously until one day, there it was. I wrote my check—I’m telling you, I’m old—and scurried back to the dorm.