Today in our continuing book study of The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published [EGGYBP], we look at the pitch.

There are two kind of pitches: 1) the elevator pitch, which is over by the time the elevator gets to the next floor, and 2) your long-form pitch. [p.70]

I keep trying to come up with a snappy elevator pitch:

- “Art & Fear only funny”?

- “How to Write a Novel in 30 Days for slackers”?

- “Twilight, but well-written. And no vampires”?

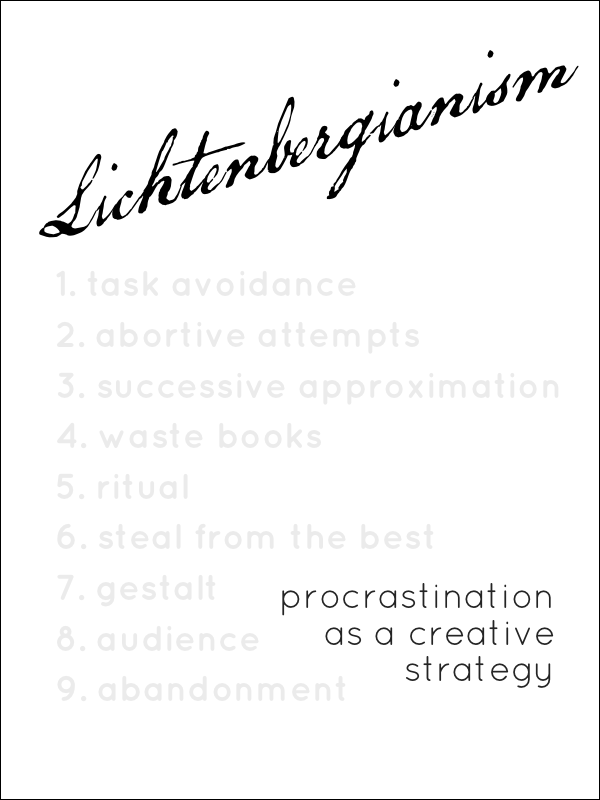

Perhaps, as the authors1 also suggest, my subtitle is the elevator pitch: “procrastination as a creative strategy, or how I stopped worrying and learned to love doing it wrong.”

The long-form pitch is no less simple. It’s supposed to be a paragraph or two, but still under a minute.

How about:

In 2007 a small group of creative amateurs founded a society dedicated to celebrating their procrastination and found, to their amazement, that their productivity improved. Now they share the secret of their success with nine “precepts,” ways to re-organize your thinking about how you create and why. Sometimes counter-intuitive and usually amusing, their strategies distill some of the most obvious secrets of the creative process to free you from your own mindblocks.

Hm. How about:

Sure, you can buy a book to help you cure your procrastination, but why would you? Lichtenbergianism: procrastination as a creative strategy frees you from the worry and the guilt—and shows you how to use your bad habits to become more productive in your creative life. No matter whether you’re a writer, an artist, a composer, a programmer, a gardener, or any other creative type, the Nine Precepts of Lichtenbergianism will give you ways to rethink your creative habits and give yourself permission to succeed—by failing!

That’s better, and more in sync with the tone of the book.

Tomorrow is better! That’s the motto of the Lichtenbergian Society, a group of creative men who bonded over their shared tendency to procrastinate and found that they became more productive because of it. Now Lichtenbergian chair Dale Lyles shows you how you, too, can stop worrying about your bad habits and learn to love your own creative process. Whether you’re a frustrated writer, artist, composer, gardener, or programmer, you’ll find new ways to think about how you create and why, from Task Avoidance to Successive Approximation to Ritual to Abandonment—if you give yourself permission to fail, you give yourself permission to create. It’s that simple!

One more:

Are you a creative genius? No, only Mozart is a creative genius, and you are not him. But you are creative—yes, you are, admit it—and you want to overcome your fears and your bad habits so that you can write that novel/paint that painting/compose that song/program that app. Lichtenbergianism: procrastination as a creative strategy gives you nine Precepts, ways to restructure your thinking about how you create and why so that you can just get to work and create the work of your dreams. But not today. Tomorrow is better.

And I’m spent.

—————

1 I keep saying “the authors” because it’s easier than typing out their names: Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry.

I will admit to having been told already that the title sucks and won’t survive an agent/editor/publisher. I will resist while I can, of course, because the whole core of the book is how the Lichtenbergians became more productive through the use of the Nine Precepts (although of course the Precepts are ex post facto developments).

I will admit to having been told already that the title sucks and won’t survive an agent/editor/publisher. I will resist while I can, of course, because the whole core of the book is how the Lichtenbergians became more productive through the use of the Nine Precepts (although of course the Precepts are ex post facto developments).