Today I want to ramble through one of the threads that went into building the units in the 5th grade U.S. History curriculum.

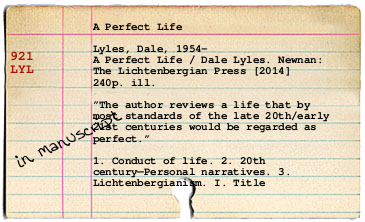

The whole thing was part of my effort as media specialist at Newnan Crossing Elementary School (1997-2011) to support active learning and direct assessment in the curriculum, something the Powers That Be said they wanted but never actually supported.[1] I called it the Enriched Thinking Curriculum [ETC] because catchy.

The ETC in turn sprang from my work as media specialist at East Coweta High School (1981-1997), where I and a secret squad of teachers began learning on our own about the new theories of learning/instruction that were beginning to filter out of solid research all over the place. (We called ourselves the Curriculum Liberation Front, and we actually operated in semi-secret: the principal knew what was up, but the asst. principal actually in charge of curriculum was not in the loop. Her métier was textbooks.)

One of the main ideas of those days was to work towards actual performance assessment, i.e., what should the kid be able to do with any knowledge you were trying to pour into his head. The state of Georgia at the time was making the transition from the Quality Core Curriculum [QCC], which was all stuff the kids needed to know, to the Georgia Performance Standards [GPS],[2] which purported to shift us over to making sure the kids could perform in the competitive new world economy.[3] The ETC was part of making that shift.

My favorite source of research on the topic was Robert Marzano, co-author of several important books on the topic, Dimensions of Learning, A Different Kind of Classroom, and Assessing Student Outcomes. I bought thirty copies of each of these for teachers to check out and read as they struggled to work with me. It would be interesting to find out if they’re still in the collection.

In Assessing Student Outcomes, the authors provided four-point rubrics for a host of standards based on the five Dimensions, but in order not to overwhelm my learners (the faculty), I selected sixteen standards from three areas in the fifth dimension (Habits of Mind) on which to focus our efforts. (The other dimensions were concerned with attitudes towards learning, and the acquisition and deployment of knowledge.) These included:

- information processing standards

- effective communication standards

- productive habits of mind standards

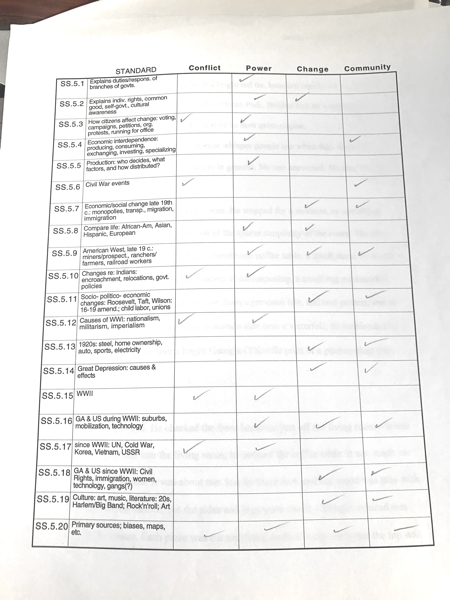

The deal was that in designing your unit/lesson, you would select two or three of the sixteen standards to assess, taking care throughout the year to hit all of them. Content assessment was separate from these, i.e., knowing that the Civil War started in 1860 was one thing, but being able to “recognize where and how projects would benefit from additional information” was a different thing. The idea was that when you constructed a lesson to assess the latter, the kid would learn the former in the process.

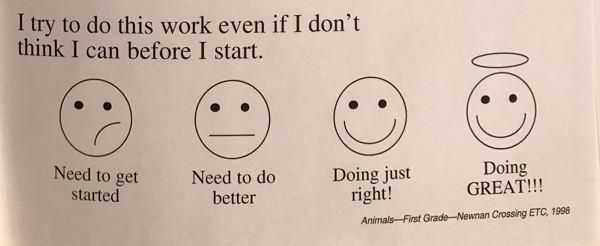

A quick example: a first grade objective was to “identify animals and their habitats.” We developed a lesson in which students would attempt to sort animals they researched into the appropriate habitat in their zoo, which was a bulletin board display. We’d give them a flock of pictures of animals; the kids had to look through books to identify the animal’s habitat, then place the picture in the appropriate habitat on the bulletin board and explain why it went there.

The productive habits of mind standard was “pushes limits of own knowledge and ability,” which we defined as “keeps looking for animal and its habitat even if he/she doesn’t find it in the first few books [in which he/she looks].” We explained that standard to them and how they would be grading themselves after the project was over with a handout with all three standards on it, each with a series of what we now call emojis: Need to get started/Need to do better/Doing just right!/Doing GREAT!!!, which corresponded to the 1–4 scale of the actual rubric. (Older students would get the actual rubrics, worded in first person for greater impact.

The productive habits of mind standard was “pushes limits of own knowledge and ability,” which we defined as “keeps looking for animal and its habitat even if he/she doesn’t find it in the first few books [in which he/she looks].” We explained that standard to them and how they would be grading themselves after the project was over with a handout with all three standards on it, each with a series of what we now call emojis: Need to get started/Need to do better/Doing just right!/Doing GREAT!!!, which corresponded to the 1–4 scale of the actual rubric. (Older students would get the actual rubrics, worded in first person for greater impact.

The important thing about these habits of mind standards was that you introduced them as you introduced the lesson, talked about how the students would meet them, give them the rubric to start with, and then do quick checks during the lesson: how are you doing on rubric x, everybody? Every time we did this, the kids upped their efforts and their abilities.

In the unit on CONFLICT, the third lesson was to construct a classroom timeline of U.S. History 1852-1996 by creating cards with info on them and arranging them along the timeline, embedding the wars the U.S. fought and giving them context. The effective communication standard was “The student creates quality products.” The rubric the kids got was:

I create quality timeline cards.

4 I create timeline cards that are even better looking than they need to be.

3 I create timeline cards that look like the good examples we discussed in class.

2 I create timeline cards that do not meet one or a few important standards.

1 I create timeline cards that do not address the majority of standards we discussed in class.

You can see how in getting this timeline built, we would be providing context for the entire year, for all four units. By the time we got to the unit on POWER and began discussing the 19th Amendment, students would already know that we had just emerged from WWI and that bunches of things had altered the landscape. You can also see that providing the kids with a way to measure themselves, they would begin to assume responsibility for their own learning rather than sitting there and shedding the state’s preferred factoids like so many wood ducks in a summer storm.

You can see how in getting this timeline built, we would be providing context for the entire year, for all four units. By the time we got to the unit on POWER and began discussing the 19th Amendment, students would already know that we had just emerged from WWI and that bunches of things had altered the landscape. You can also see that providing the kids with a way to measure themselves, they would begin to assume responsibility for their own learning rather than sitting there and shedding the state’s preferred factoids like so many wood ducks in a summer storm.

The other two standards were I accurately determine how valuable specific events may be to creating the timeline and I listen to and evaluate feedback to decide if I need to change my approach to choosing an event to include on the timeline. Because we really preferred Wilbur and Orville Wright make the first flight at Kitty Hawk, NC to Arthur S. Crankshaft wins Wimbledon.

Again, this post is too long, so one more before we’re done.

NEXT: The Big 6

—————

[1] And here I am referring to state and federal lawmakers who never did anything but say one thing and test another.

[2] Before you cringe at that acronym, consider Virginia’s Standards of Learning. Every committee everywhere needs to have a 12-year-old boy to vet these things.

[3] Because they continued to test only for stuff, we never made that shift. Georgia is now shifting again, to the Standards of Excellence. Since I’ve hopped off that pendulum, I cannot advise or consent to whatever the hell it is they’re spinning their wheels about this time.

There are five units in my folder on CONFLICT. Each would probably have taken three to five days in the media center plus time in the classroom. I note that the date on these pieces of paper is 1998, so our internet access would have been rudimentary. Google didn’t exist. Yahoo did, but it was a hierarchical search engine.

There are five units in my folder on CONFLICT. Each would probably have taken three to five days in the media center plus time in the classroom. I note that the date on these pieces of paper is 1998, so our internet access would have been rudimentary. Google didn’t exist. Yahoo did, but it was a hierarchical search engine.

OK, let’s look at that, because there’s a lot of sleight of hand going on here.

OK, let’s look at that, because there’s a lot of sleight of hand going on here.