On the Nature of Reading Caves

At Newnan Crossing Elementary, we’ve been celebrating Read Across America, as is our wont, with our Reading Caves event. I thought it might be appropriate to talk about the theory and practice of this curious cultural artifact.

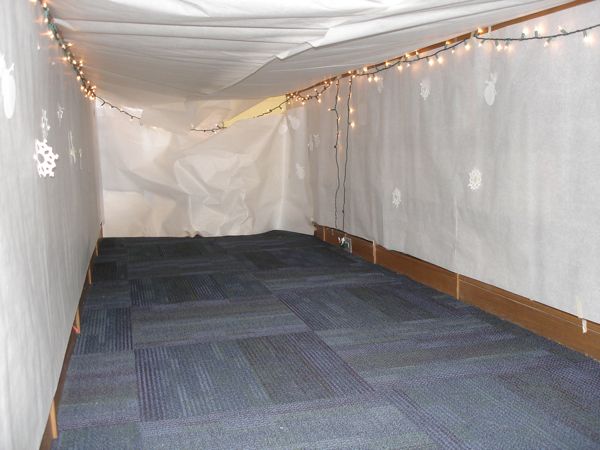

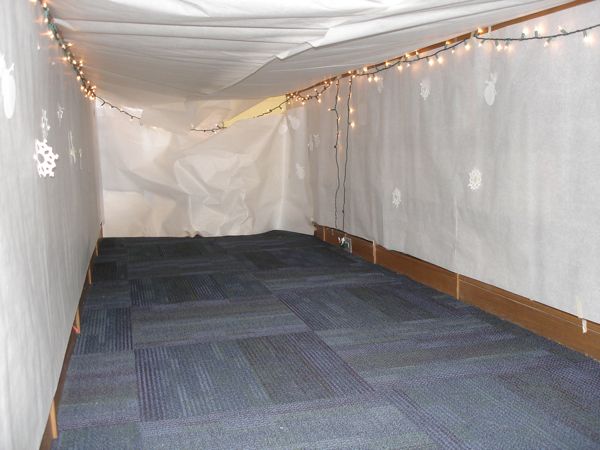

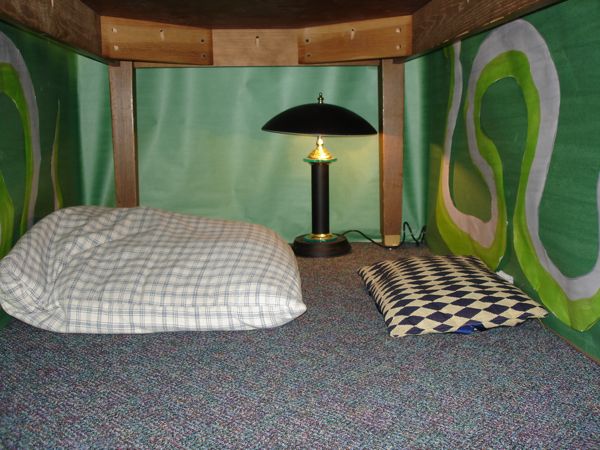

First a photo of this year’s caves:

As you can see, teams of teachers come in and transform the media center with bulletin board paper and fripperies. The idea is that students will come in and secrete themselves in one hidey hole or another and read for a short time. It’s just something out of the ordinary and fun.

But why? Why don’t I bring in multitudes of volunteers to read books, usually something by Dr. Seuss, to classes all over the school?

I used to do that, actually. As the school got larger, however, it became more and more of a problem to line up the number of volunteers needed, then match their availability to our insane patchwork schedule all over the building.

And then one year, I forgot. I looked at the calendar, and it was February 25, and I had done nothing about Read Across America Day on March 2.

I panicked.

But then, somehow, I remembered a thing I had read years before.

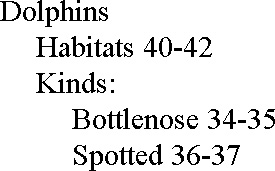

The Theory of Reading Caves

A Pattern Language, by Christopher Alexander, et al., is a tome published in 1977, and it bears every hallmark of the sensibilities of the 1960s and their aftermath: utopianism, rejection of urban/corporate life, respect for older ways, optimism, etc., etc. Large parts of it belong to the “isn’t it pretty to think so?” school of planning, but a great deal of it is not only heartfelt, but valid.

The book is essentially a grammar of design for living spaces: towns, buildings, homes, neighborhoods. More than 250 ‘patterns’ in this grammar are presented, hierarchically listed and interlinked. The patterns are derived from the authors’ observations about how healthy cultures live(d), and many are precisely archetypal.

Late in the book, p. 927-929, we are presented with a detail pattern: 203 CHILD CAVES. I will quote the pattern in its entirety:

Children love to be in tiny, cave-like places.

In the course of their play, young children seek out cave-like space to get into and under, old crates, under tables, in tents, etc. […]

They try to make special spaces for themselves and for their friends, most of the world about them is “adult space” and they are trying to carve out a place that is kid size.

When children are playing in such a “cave”, each child takes up about 5 square feet; furthermore, children like to do this in groups, so the caves should be large enough to accommodate this: these sorts of groups range in size from three to five, so 15 to 25 square feet, plus about 15 square feet for games and circulation, gives a rough maximum size for caves.

Therefore:

Wherever children play, around the house, in the neighborhood, in schools, make small “caves ” for them. Tuck these caves away in natural left over spaces, under stairs, under kitchen counters. Keep the ceiling heights low, 2 feet 6 inches to 4 feet, and the entrance tiny.

I don’t think I need to provide a lot of proof or defense for pattern 203: who among us has not thrilled at the receipt of a refrigerator box? I remember that one reason I looked forward to school being out each summer was that I could prevail upon my father to go to Maxwell-Prince Furniture (“Drive a little and save a lot,” a slogan necessitated by the fact that they were not on the Court Square but, gasp!, nearly a whole mile away out on Hwy 27, at the Hospital Road intersection) and get me a box. It would become my Fortress of Solitude for weeks.

So, in my panic and desperation at having not scheduled a single reader for the school, I boldly announced a new initiative: Newnan Crossing Reading Caves!

That first year was more than a little desperate. I pulled the thing together literally overnight, bringing in sheets and swaths of fabric; lamps; pillows. I turned over tables and enveloped them in bulletin board paper. I turned the book aisles into long, narrow enclaves. I borrowed the parachute from the gym and draped it over tables and the couch. I borrowed materials from teachers. The whole thing was quite lame.

And it was a huge hit. The kids didn’t see the tape and bulletin board paper, nor did they see how desperately cheesy it was: they saw CHILD CAVES, and they were ecstatic.

At that point, Newnan Crossing was pushing 1,000 students, and it was clear to me that Reading Caves was a much more practicable solution to Read Across America Day than the nightmare that scheduling volunteers had turned into. We went with it.

Reading Caves in Practice

Since that first year, I have invited teachers to join in the fun. Those who choose can volunteer to put up a Reading Cave, and they choose their theme. On the afternoon beforehand, they come into the media center and transform it. For the next two days, media center traffic comes to a standstill: it’s silent reading time in here, and besides, most of the shelves are covered by the caves.

After the teachers have set up theirs, I’ll go around and do the table thing to fill in the gaps. (I also have my own major Cave to put up.)

We run Reading Caves for two days so that most classes have a chance to come in and spend a while reading. After each class comes in, I give them four minutes to explore, and after a one-minute warning, they have to sit and read. (This year, I created two sound files, one with an introduction, and the one-minute warning, followed by a “sit and read”; and a 20-minute loop that had nothing in it but a chime to end the session about three minutes before the end. During the entire day, I play quiet music, this year all space music. Drove me nuts.)

The four minutes are insane: we usually have two classes at a time, and they go nuts as they explore one cave after another. And then when the one-minute warning sounds, it becomes bedlam. Now they have to choose which cave to sit in, and the friend/clique factor kicks in, and lo! there is much squealing and running.

And then it’s quiet for about ten minutes as they settle in and start reading. For the little kids, that’s enough time. For the older ones, I need to find a way to have longer sessions, because they’re just getting into it when the chime instructs them to close their books and “return to real life.”

They leave on a high, chattering about how much fun they’ve had. It’s pretty neat: a really big response for not a lot of work.

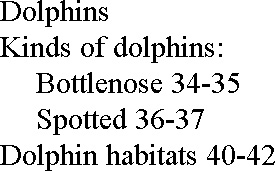

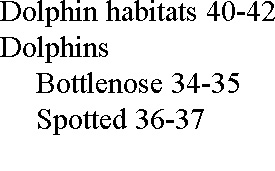

The caves can be elaborate, or they can be simple as pie. Here are some from this year and the past:

Charlotte’s Web, complete with bales of hay, the web, troughs, and a fence of yarn (that no one could see and which we finally had to take down for safety’s sake). If you look in the trough on the right, you can see a little brown Templeton. Kids climbed up on the tables inside, somehow managing to not knock off all the chairs that were perched up there with them, holding up the roof.

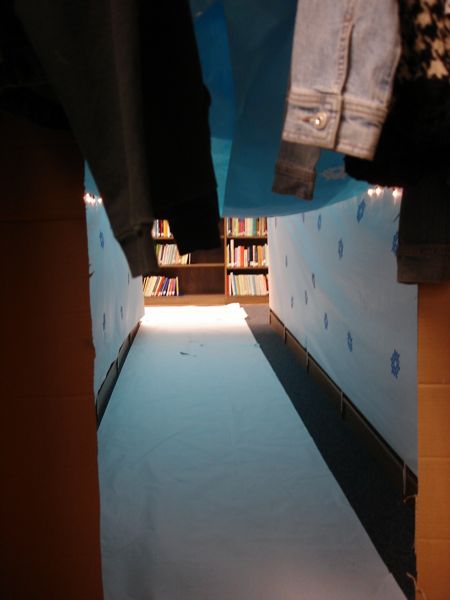

The fifth grade’s Iditarod cave. Simplicity itself, but because you entered from one aisle and had to crawl all the way down and around (in a U-shape), it was very popular. Also popular, and pictured up at the top of the post, was a Twilight cave. How do kids this young even know about that accursed phenomenon? That cave was actually two: a cave and a den (for the werewolves.)

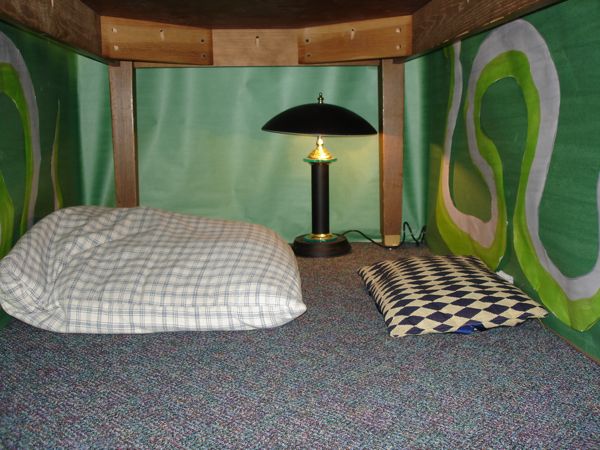

My 100 Book Club cave. Not very flashy, but it was comfortable. More than a few kids found it cozy:

I have these large pieces of cardboard that were donated several years ago by Multec, a local company that makes packaging. I’ve saved them and use them every year, so my cave has actual walls. I’m thinking of ways to make it more complex and interesting next year. And I hold them together with Mr. McGroovy’s Box Rivets, a wonderful, wonderful invention.

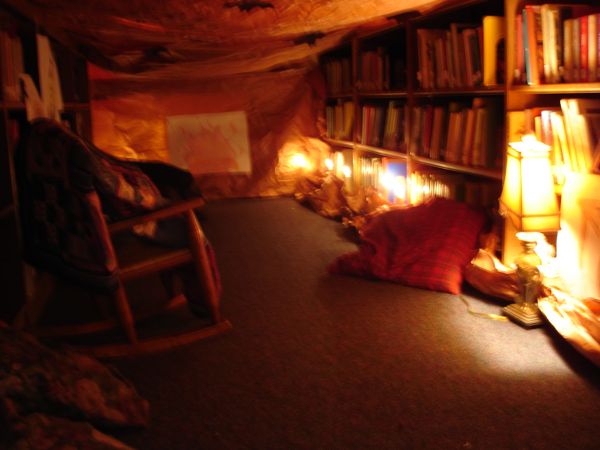

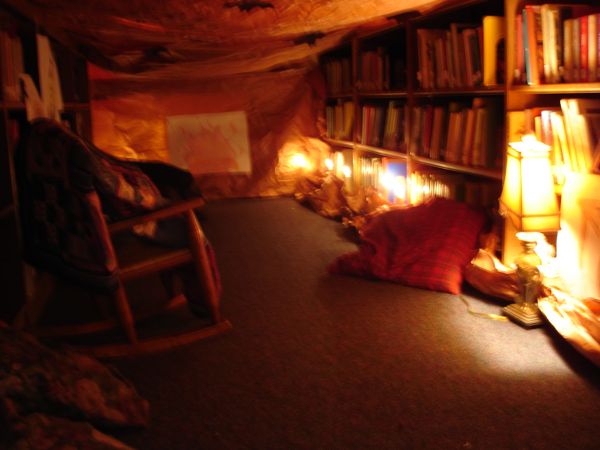

One year, I did a Hogwarts. Here’s the Slytherin common room from that cave:

Above that was the Gryffindor common room. You entered the cave by crawling under a table; that table had the Great Hall on top. I had house banners hanging, and great portraits all over the walls.

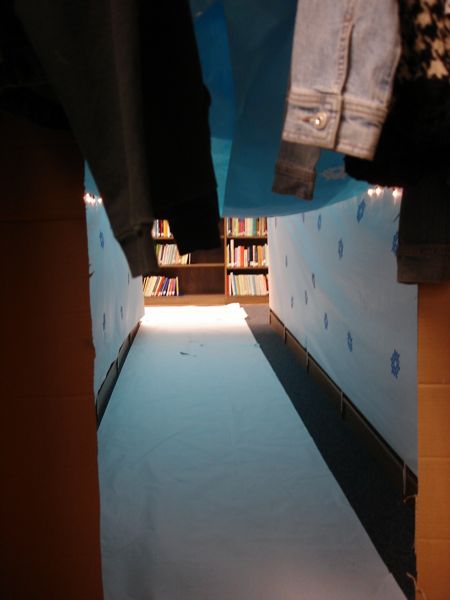

Here’s a glance at the exterior, beyond the Three Little Pigs houses:

The houses of the Little Pigs were made of PVC pipe, covered in fabric. Each would hold one child.

My all-time favorite was the year 5th grade did Narnia. You entered through the Wardrobe, of course:

There was a stretch of Narnia in winter:

Then you turned the corner, and there you were in Mr. Tumnus’s house:

Pretty spectacular.

Some practical considerations: since we turn out the lights, you will need to consider how the children will see to read. There are outlets nearly everywhere in the media center, so power is not really a problem. I made that mistake with the “Blake Leads a Walk on the Milky Way” cave two years ago: the all-black and black-light lit space was very cool, but no one could see to read.

You have to consider supervision. Make sure there’s a way an adult can see into the space and check on things. We had to cut a flap in the Iditarod cave this year for that reason. Otherwise, the more closed in, the better. One reason the 100 Book Club cave was not as popular as it might have been was that it was largely open.

Seating is an issue. This year’s Magic School Bus looked great, but was not very popular because there were no cushions. The same went for the secondary parachute cave. There was just bare carpet, and not many kids found it appealing.

Like A Pattern Language suggests, room for more than one student is good, but more than five is just not cozy. Still, most of the one-kid caves were occupied, because there are some students who are serious about the reading part and don’t want the distraction of other kids.

The cave does not have to be elaborate:

This one, just a table on its side draped with paper, was occupied more than half the sessions. If I had gone a little more origami on it and closed the front a bit, it would have been even more popular.

I’m already planning next year’s Reading Caves. Let me know if you’d like to join in.