I may or may not have started notes on Lichtenbergianism: procrastination as a creative strategy this afternoon in the labyrinth.

Category: Lichtenbergianism

Lichtenbergian goals, 2015

Seven Dreams

Definitely tops on the list: The challenge of writing an opera has been both invigorating and frustrating, but I think the results so far are worth continuing. It would be nice to think that I will have this finished by the end of the year. Nice, but not probable.

3 Old Men

Another success from this year that I want to continue to work on. My experience at Alchemy with the 3 Old Men gang was profound, and I want to find ways to enhance/expand our theme camp. [Hint: it involves a deer stand and a megaphone.]

Five Easier Pieces

Maybe.

Christmas Carol

I spent the first half of this year rebuilding the original piano score for A Christmas Carol so that it could be played by a small, live ensemble. That proved to be an un-possible task for Newnan Theatre Company, and the results were not pretty.

So I will spend this year a) finding an affordable software music sequencer that works like the old EZ•Vision sequencer did; b) learning to use it; and c) completely rescoring Christmas Carol again with a full orchestral accompaniment. And d) directing the show next year.

SUN TRUE FIRE

Definitely a back burner project, since I have rather enough to be going on with. But I’m determined to develop better work habits, so that if I don’t have anything else on my plate on any given day, I can just pull this project out and spend an hour or two on it. (vid. sub.)

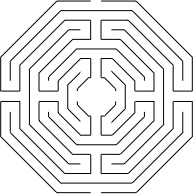

design & construction of labyrinths

I began a notebook earlier this fall wherein I began a serious study of the topology/design of labyrinths. It is oddly harder than it looks, but I’m beginning to crack the code. I want to keep digging into the process so that I can easily respond to any landscape or user need with a design that fits the bill.

general work habits

My usual process is to focus very hard on a single project, with just enough Lichtenbergian distractions to avoid being placed on the far end of the autism scale. I’d like to change that. I’d like to be able to turn my attentions to several projects in rotation, or even at random, without grinding my mental gears. I’d also like to be able to say that I have kept working instead of sitting around twiddling my thumbs when one project is at a standstill.

In other words, when Seven Dreams bogged down, why didn’t I simply write an Easier Piece?

Astute readers will have noticed that I did not include the symphony on my goals. Maybe I forgot about it, maybe I didn’t.

Lichtenbergian goals, 2014

Each year the members of the Lichtenbergian Society have their Annual Meeting around the fire in the Labyrinth, and part of our ritual—which involves much toasting to all the things—is setting our creative goals for the coming year and evaluating the goals we set for this past year.

All in all, I didn’t do too badly with 2014’s goals. Of course, with my permanent retirement, there’s no reason I shouldn’t have done more, but hey, it’s Lichtenbergianism.

Five Easier Pieces

Didn’t get to them. I don’t think I even took a stab at them. I certainly don’t have them.

song for John Tibbetts

This one I did. It’s entitled “Your Beauty,” and can be found here. I don’t know whether it actually works; the key to its effectiveness (if any) is in the live interpretation, and the computer doesn’t come close to being able to do that. But I think it’s solid enough.

SUN TRUE FIRE

See, here’s the thing with SUN TRUE FIRE. I was going to spend all of 2014 noodling with the text and experimenting with snippets by taking bits of other people’s music and seeing if I could replicate the effects that I admired: orchestration or harmony or counterpoint, etc. I kind of started, but then Seven Dreams of Falling came my way. As a Lichtenbergian, I was honor bound to postpone one work by creating another. SUN TRUE FIRE isn’t dead; it is sleeping.

Waste books

Another success story. I have used the Field Notes notebooks for every project, including morning pages (at which I have not been assiduous) and actual waste books (at which I have been slightly better). Some, like the notebooks on Christmas Carol or “Your Beauty,” have only a few pages in them. But I filled three notebooks with thoughts and designs and instructions and references for Burning Man, and as we keep 3 Old Men moving forward I expect to fill more. I love my notebooks.

Burning Man

Here’s the thing about Burning Man. I planned for it, I got tickets for it, my application to be a theme camp was accepted, it was golden—and then we couldn’t go. Undeterred, we pushed on to Alchemy and it was amazing. Because we were so successful there, and because we intend to keep the band together for future regional burns, I’m counting this one as my most successful goal of the year.

Christmas Carol

The goal was to reconstruct the music for A Christmas Carol for Newnan Theatre Company’s revival of the show, the first in eleven years. I did that. I delivered a complete set of scores and parts, plus the script, back in August. Due to the exigencies of community theatre, the production didn’t quite get the music back on its feet, but I got the job done. We’ll see about next year.

Next up: 2015 goals!

Ambition

You may recall that one of my Lichtenbergian goals this year was to institute a system of “waste books,” i.e., notebooks that would serve as repositories of random stuff that could later be transferred to wherever they needed to go, e.g., blogpost, letter, other notebook.

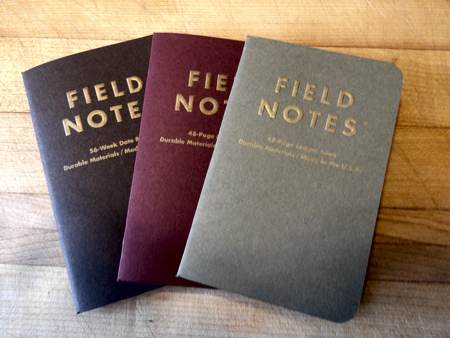

You may also recall that I subscribed to the Field Notes “Colors” notebooks, which has been really cool since every quarter I get a new set of notebooks, each a new geek-o-rific design. It’s actually a creative impetus each time, since one tends to think, “Ah, a set of notebooks with a cherry (wood!) veneer cover! I shall use those to journal my Burner experiences!” And so forth.

I’ve had a great year with my Field Notes: planning 3 Old Men for Burning Man/Alchemy; morning pages; waste books; keeping my re-orchestration of Christmas Carol on track; text and notes for John Tibbetts’ song; prepping for SUN TRUE FIRE, which was sidetracked by Seven Dreams of Falling, which has its own notebook. I planned my son’s wedding ceremony in the Arts notebook, and started a labyrinth design project in the Sciences notebook. It’s been fun.

However, I am distressed at the most recent offering, their 25th release. Each release has a name—Shelterwood, Arts & Sciences, Unexposed—and they’ve named this one Ambition. It’s stunning, beautiful, and absolutely daunting.

Love the colors. Love the gilded edges you guys! Love the gold staples.

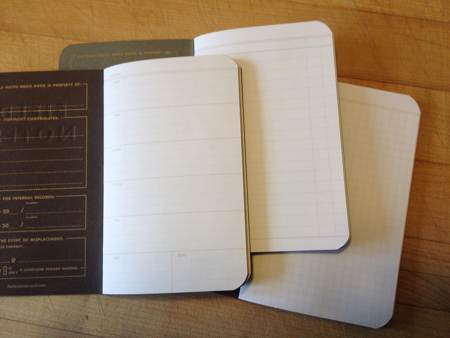

But then you open them.

AMBITION. You see what they’re about. From left to right, we have a 56-week date book, a ledger book, and a memo book.

This is serious stuff. Planning. Budgeting. Making something happen. Something big. Something important. Something consequential. They didn’t gild those edges for your paltry, quotidian concerns.

What am I supposed to do with these?? They mock me. They’re going into the archival wooden box where I will not have to look at them. I will be able to sleep at night. All will be well.

3 Old Men: mapping the field of ritual, redux, part 5

: Ritual sound & language :

What is the role of silence in the rite? … Do the people consider it important to talk about the rite, avoid talk about it, or to talk during it? Are there parts of the rite for which they find it difficult or impossible to articulate verbalizable meanings? … How important is language to the performance of the rite? What styles of language appear in it — incantation, poetry, narrative, rhetoric, creeds, invective, dialogue? In what tones of voice do people speak? … To what extent is the language formulaic or repetitious? … How much of the language is spontaneous, how much is planned?

The ritual itself, the transformation of Old Men, was done in silence, and I think it was good that way. I don’t know what others were doing, but I was soaking in the energy and trying to return it to my fellow Old Men and to the space. I think also that the visual of the Old Men performing their ritual in silence—as if we’d been doing this for years instead of for the second time in our lives—was quite compelling and beautiful.

(Think about that last bit, guys: we’d literally done the ritual only once before, at the runthrough out at Craig’s in September. We had no official way of making assignments or changes—and yet we did. More than one burner was astonished to find that we were Alchemy virgins, and a lot of their impression came from watching the solidity of the ritual. It looked ancient.)

Of course language was important to the agons—we had to engage the participant with the blessings/struggle. As far as I know, we didn’t actually codify the language there, although I don’t think anyone strayed very far from, “May I bless you?” / ”Will you bless me?” / “I offer you a struggle.” It doesn’t get much simpler than that.

And then language became critical for the experience: either our improvised blessing or theirs, and the choice of the struggle. Silence played its role as well: I never explained the struggle to the participant, just pushed into the space and did what felt right. Question for discussion: did anyone else develop specific language/actions for their versions of each agon?

As for talking about the rite, many people did and thought it was important to do so. I agree. I like to hear what people brought to the experience and what they got out of it. I think Craig’s instincts are correct that we should eventually provide a “decompression” space, perhaps with food and/or music.

Music was always welcome. Will’s Bach suites were amazing, and of course after sundown we always had Incendia for company. I do wonder how, if we added drumming, bells, or flute laying as a regular thing, that would work with Incendia going full blast.

3 Old Men: mapping the field of ritual, redux, part 4

: Ritual identity :

What ritual roles and offices are operative—teacher, master, elder, priest, shaman, diviner, healer, musician? How does the rite transform ordinary appearances and role definitions? Which roles extend beyond the ritual arena, and which are confined to it? … Who initiates, plans, and sustains the rite? Who is excluded by the rite? Who is the audience, and how does it participate? … What feelings do people have while they are performing the rite? After the rite? At what moments are mystical or other kinds of religious experience heightened? Is one expected to have such feelings or experiences? … Does the rite include meditation, possession, psychotropics, or other consciousness-altering elements? … What room is there for eccentricity, deviance, innovation, and personal experiment? … Are masks, costumes, or face paint used as ways of precipitating a transformation of identity?

Again, I think there are two rituals going on in our camp: the ritual we perform to become Old Men, and then the ritual experienced by those who walk the labyrinth. I’ll try to keep them straight as I move through this section.

I don’t know how others felt, but I for sure felt as if I were elder, priest, and occasionally a shaman while I was in our ritual. The transformation from Alchemy camper into Old Man never failed to ring true for me. I felt not necessarily exposed, but opening to the onlookers: “This is my body,” if you will. “I mark it, I draw attention to it, I show you the way in, and now I become an Old Man who can assist you. Follow.”

While officiating, I felt very calm—outside time—while at the same time alert to the participants and their choices. I found myself reviewing the original list of traits: solemnity, compassion, serenity, wisdom, openness, and groundedness, and trying to embody and project those to onlookers and participants.

Someone commented that they noticed that I smiled much of the time. Truthfully, it was a conscious decision on my part to return all the positive energy that I was absorbing to the environment. Alchemy and 3 Old Men made me very happy, and I wanted to give that back.

It is interesting that in the original post I was still dithering about the body paint and the nudity. I was fairly sure that it was what we needed, but at that point the troupe was all my theory and no real practice. Needless to say, it was amazing to perform and to watch. I’ll have more thoughts about this element in a couple of days when I talk about ritual action.

I am very curious as to what people’s feelings were when they walked the labyrinth. That’s one thing I want us to do better in the future: collect responses, either through interviews or with some kind of book people could write in.

Was there room for “eccentricity, deviance, innovation, and personal experiment”? You betcha. I think that’s one of the strengths of 3 Old Men, that we opened the labyrinth for others to build their own experiences. It never bothered me to see people romping through it, or stepping over the ropes to be ‘clever’ in ‘finding the way out.’ Everyone brought what they needed and took what they needed.

As I said in the original post:

I expect to see people walking the labyrinth in silence and prayer; singing and dancing; giggling and inattentive; naked; stoned and lost; smirking and cynical; hurriedly. I expect drummers and other musicians to join us. I expect people to be puzzled or put off by the offer of an agon; I expect some to accept it gratefully, with tears, with joy. I expect to be quizzed—”What is this about? How do I do it?” I expect to be ignored. I expect to have others expect me to be something more than I have offered.

And I expect to be transformed by all of it, to learn more about my identity as an Old Man.

And so it was.

3 Old Men: mapping the field of ritual, redux, part 3

I’m revisiting my explication of 3 Old Men in terms of Ronald Grimes’ Beginnings in Ritual Studies.

: Ritual time :

At what time of day does the ritual occur—night, dawn, dusk, midday? What other concurrent activities happen that might supplement or compete with it? … At what season? Does it always happen at this time? Is it a one-time affair or a recurring one? … How does ritual time coincide or conflict with ordinary times, for instance work time or sleeping time? … What is the duration of the rite? Does it have phases, interludes, or breaks? How long is necessary to prepare for it? … What elements are repeated within the duration of the rite? Does the rite taper off or end abruptly? … What role does age play in the content and officiating of the rite?

The Great Ritual, i.e., Burning Man/Alchemy/wherever, determines when the 3 Old Men emerge from the mists and perform their ritual.

As I posted earlier, we had decided on dawn, sunset, an hour after sunset, and midnight as the four times we would perform the ritual—but the exigencies of weather convinced us to dump the dawn and add noon instead right off the bat.

The fact that I misunderstood the chart I used to determine sunset each day (neglecting to account for DST) meant that we had submitted a schedule to the central committee that had us out there at sunset and an hour before. (At our very first performance of the ritual, it seemed to me that it was very much daylight; nothing like taking your clothes off in front of a steady stream of traffic arriving at the burn.)

But we stuck with it, just in case someone out there had downloaded the schedule and came looking for us. It worked, although I think next time we will go with the actual sunset and an hour afterwards. We look awesome by the flickering of the tiki torches.

I’m also fine with our canceling ritual performances when it’s too freaking cold to smear liquid kaolin over our naked bodies, although that last performance with the blankets/shawls was great too. We could legitimately make actual shawls/serapes to wear if it’s chilly.

As for supplementary or competing activities… Well, that’s what makes it a burn, ne-ç’est pas?

I like the fact that we were available most of the time to assist those walking the labyrinth even when we aren’t out there in full regalia. I like how people felt comfortable sitting and chatting. I think our canopies could be better deployed as a decompression area.

In the original post, I talked about the Great Ritual of Burning Man vs. the small ritual of the labyrinth. I think the same concept can be applied to 3 Old Men itself: the Great Ritual of the officiants vs. the open labyrinth the rest of the time. Four times a day, the Old Men would take their places at the entrances to the labyrinth and offer the agons to participants. Otherwise, the labyrinth lay open for exploration and meditation. I think this worked. I do want to continue to recruit Old Men so that we can offer more/longer sessions. I think it would be great if we were “open,” so to speak, the entire time Incendia was up and running, for example.

I think we ended up manning our posts about 30 minutes each time. It seemed adequate; more officiants would allow us to tag team and keep going.

As for “age” as a determinant for participation, I really like the fact that all of us were over 45 at least. For me, the entire experience was a profound meditation on being an Old Man and how powerful that was. I don’t know how I would feel if a young man (say, the kid who stripped and painted himself) asked if he could camp with us or officiate.

3 Old Men: mapping the field of ritual, redux

Back in March, I blogged a lot about the theory and practice of the 3 Old Men ritual troupe as I prepared to head out to Burning Man. This was before I found out that we were not able to go this year. We did, however, go to Alchemy, the Burn-like event in north Georgia, and as I reread those posts from March I thought I should go back over some of the ideas and talk about them as they eventually played out in real life.

The background is Beginnings in ritual studies, by Ronald L. Grimes, and I did a series of posts on his chapter of “mapping the field of ritual.” What I’d like to do is spend a few posts looking at his questions again and see if there were any unanswered questions or surprises in the event itself.

: Ritual space :

Where does the ritual enactment occur? If the place is constructed , what resources were expended to build it? Who designed it? What traditions or guidelines, both practical and symbolic, were followed in building it? … What rites were performed to consecrate or deconsecrate it? …. If portable, what determines where [the space will next be deployed]? … Are participants territorial or possessive of the space? … Is ownership invested in individuals, the group, or a divine being? Are there fictional, dramatic, or mythic spaces within the physical space? [Grimes, p. 20-22]

Rather than the vast and inhospitable Black Rock Desert, Alchemy takes place on a green tract of farm land in North Georgia. Hilly, wooded, with roads, a lake, and even camp showers, it’s not quite as an austere environment as Nevada. It did require—when I submitted our application to be considered as a theme camp—knowledge of the territory, which I didn’t possess but on which my fellow Alchemists were happy to advise me.

As it turned out, we were placed right at the entrance to the site. There’s a giant windbreak/hedge across the eastern side of the property, and the main road cuts through it—and there we were, first camp on the left. Nice, flat, and accessible. At first I thought we might have been slighted as newbies; for the first 36 hours of our experience, there was a steady stream of traffic pouring past our camp, not quite conducive to quiet meditation. But the team leader who actually placed us there told me he thought we would benefit from the foot traffic to our neighbors across the street, Incendia, and he was right.

Consecration was simple—I smudged the circle and the center, and then our team members, and we were off. In the future I would like to incorporate that moment of sacralization for each time we perform the ritual.

In March I talked about the Great Ritual of Burning Man itself and of the smaller rituals such as 3 Old Men. Because of the smaller scope of Alchemy and shorter life-span (both in terms of longevity and of duration), I did not sense a Great Ritual there other than the liminal experience of crossing that boundary and committing to life with the dirty freaking hippies for four days. Lots and lots and lots of smaller rituals, of course.

We had interesting territorial issues, in that the 3 Old Men’s performance was compelling, but daunting: it turned out that many passers-by were so impressed by the ritual that they regarded entering the labyrinth as a real test. Most looked interested but avoided participation. As we worked through the weekend, we developed ways to make it clear to people that they were welcome, and as word spread we got an uptick in participation. I think as we continue to attend Alchemy and other events, we will build a reputation and more people will be willing to take the plunge. Still, I’m kind of impressed that what we had made it clear that this was not a silly thing.

Ownership did become invested in the group. While I think everyone still looks to me as a guiding force, I was delighted that everyone felt comfortable in creating new aspects to the experience.

Besides the labyrinth itself being a mythic space, the center became more important as a focus, a fact I’ll talk more about in the section on Ritual Objects tomorrow.

3 Old Men: skirts & stakes

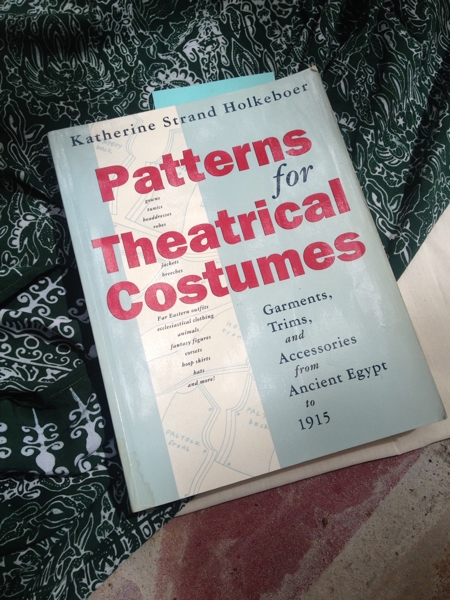

Hello, my old friend Holkeboer:

Back in the day, in costume design class, Dr. Jackson Kesler—who is a god—had us do “book reports” on a long list of resources. We evaluated them for usefulness, and that list of books became our go-to library for the rest of our lives. (Which was his intent, and which is why he is a god.)

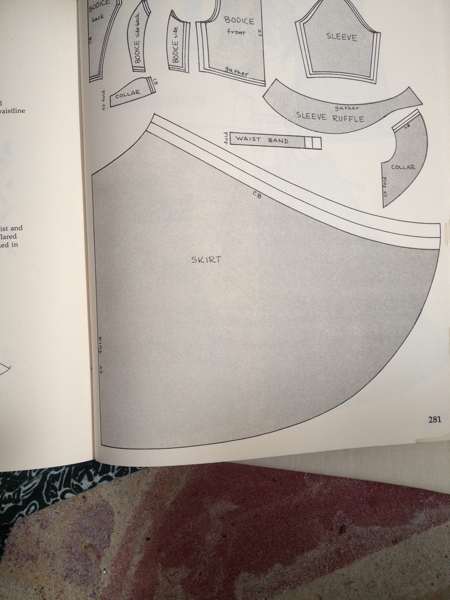

Patterns for Theatrical Costumes was not published until 1993, but it would have been one of the tops on the list. It’s skimpy on details, but it’s great for basic shapes/drapes/silhouettes:

So there’s the basic pattern for the ceremonial skirt that the 3 Old Men wear as officiants for their labyrinth.

Did you know that a new patio is a great costume shop space?

Five yards of muslin. Step One of any costume, Dr. Jackson Kesler taught us, is to mock it up out of cheap fabric. We had bolts of some cheapass cotton sateen that we called “grahdoo green” which was our preferred mock-up of choice. (Generally speaking, the mock-up—after we used it for fitting and then disassembled it for the pattern—became the lining of the actual costume.)

It being a beautiful day, I thought I might as well set up the entire shop:

All told, it took me about an hour and a half to get the first mock-up put together. More later.

That was yesterday. Today, I removed the labels from 144 tent stakes:

Three plastic tubs, 144 16-inch stakes, water. And then I peeled the labels. Sometimes the work of ritual troupes is merely tedium.

Burning Man: Order. Community. Transformation. Part Two

Communitas is the second of the products of ritual.

It is easy to see why this is so: for a public ritual such as 3 Old Men, people come together to participate. They have agreed, corporately, that this action is good and appropriate and that it must be done.

And by doing so, they bond themselves into a community. They are part of something larger than themselves. Indeed, they have crossed that line of liminality into something universal.

Note that this communitas is not tribalism (although certainly tribalism uses ritual to reinforce itself). Those who commit to a ritual come to understand that they are part of the Order created by the ritual, and more importantly, the others in the ritual are part of the same Order. They are a Community.

With the 3 Old Men, we offer the Burning Man community a ritual of passage: a hero’s journey from the outside to the center and the return, ending with an agon that assumes meaning according to the metaphor constructed by the participant.

One thing that interests me about our ritual is that it differs from the experience of a regular labyrinth. A regular labyrinth offers one path in and one path out, usually the same path; the ritual is a meditation, seeking meaning and metaphor in the walk, undisturbed by conscious choices. In our labyrinth, on the other hand, choice becomes an integral part of the journey. I don’t know if you’ve traced the pattern, but each of the four paths branches twice before returning to itself. It is not a maze; there are no dead ends, and you cannot get “lost,” but you must at least pick a path (twice) on your journey to the center—and that’s after picking which entrance to use.

Once in the center, choosing an exit reverses the process, only this time, your choice involves a choosing, if that makes sense: more than the direction you exit, there are officiants standing outside three of the four exits, each offering a different agon. Indeed, choosing to undergo an agon or not becomes a major part of the ritual.

More: the question arises of what happens when you have chosen to exit towards the officiant who offers a blessing, for example, and while you are making the journey outward, the officiants make their procession to another entrance. Do you continue your path, exiting to an agon (or the absence of one) different from the one you had hoped to encounter? Do you stop, return to the center, and exit to your original choice? Can you do that?

Thus those who participate in the 3 Old Men’s ritual will find themselves involved in a communitas which they may not completely understand—it makes no demands of them to join a “community,” but it does lead them into a confrontation with a structure offered by three mysterious elders, a structure that asks them to regard the choices they make—and the choosing—and to construct their own meaning of those choices. It offers them a brief liminal experience in the middle of the hurly-burly of Burning Man, and my hope is that that’s a good thing.

Tomorrow: Transformation.