In Lewis Hyde’s Trickster Makes This World: mischief, myth, and art, he has a chapter called “Speechless Shame and Shameless Speech” in which he posits that shame is linked to societal rules about speech and silence, and that those rules have an “ordering function,” not just of society but of the body and the psyche as well.

He quotes from Hunger of Memory, the memoir of one Richard Rodriguez:

The normal, extraordinary, animal excitement of feeling my [teenaged] body alive—riding shirtless on a bicycle in the warm wind created by furious self-propelled motion—the sensations that first had excited in me a sense of my maleness, I denied. I was too ashamed of my body. I wanted to forget that I had a body because I had a brown body.

Hyde goes on to note that “…an unalterable fact about the body…”—in this case, Rodriguez’s brown skin— “… is linked to a place in the social order,…”—i.e., less than white skin— “… and in both cases, to accept the link is to be caught in a kind of trap.” [1]

The Trickster, however, subverts that trap. Remember that Trickster = Raven, Coyote, Br’er Rabbit, Shiva, Dionysus, Jesus.

Or Old Men.

If you take Rodriguez’s passage and substitute old for brown, you can see another source of the power of 3 Old Men’s ritual at burns:

Wise to the tricks of language, the [Trickster] refuses the whole setup—refuses the metonymic shift, the enchantment of [societal] story, and the rules of silence—and by these refusals [he] detaches the supposedly overlapping levels of inscription from one another so that the body, especially, need no longer stand as the mute, incarnate seal of social and psychological order. All this, but especially the speaking out where shame demands silence, depends largely on a consciousness that doesn’t feel much inhibition, and knows how traps are made, and knows how to subvert them.[2]

That’s long and complicated. But what it means for us is that rather than be complicit in the role that society has constructed for the words an old man, the 3 Old Men troupe rejects that metonymy— “a kind of bait and switch,” Hyde says, “in which one’s changeable social place is figured in terms of an unchangeable part of the body”[3]—in this case, our aging male bodies—and instead substitutes a different reading.

This reading (about which you can read my original thoughts here) also links into Hyde’s contention that any social structure of meaning undergoes “purification” as it continues to create order, discarding undesirable or repellent bits, i.e., “dirt.” He contends that in an eternal dialectic, the Trickster takes the dirt, the waste, the excluded detritus of the system and revivifies the system by breaking it open and throwing the dirt back in.[4]

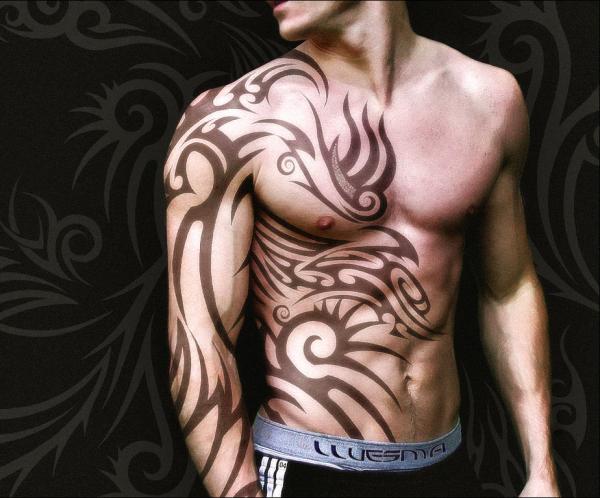

Thus, our society’s ideals of beauty and power have over the centuries focused more on the youthful male body—sleek, virile, strong—and rejected the aching joints, sagging breasts, and protruding bellies of the old. 3 Old Men uses its ritual to call attention to those attributes of “oldness” and to overturn and recreate that societal order in the labyrinth, and then to include that society which excluded the former “dirt,” by opening the labyrinth to the journey of others, ending with our agon encounters at the boundaries.

Ritual: Order. Community. Transformation.

—————

[1] Hyde, p. 169

[2] ibid., p. 171

[3] ibid. p. 170

[4] In a stunning bit of synchronicity, the chapter after “Speechless Shame” is “Matter Out of Place”: dirt is that which is out of place when we create our order. Matter out of place, or MOOP, is of course a key concept in Leave No Trace, one of the 10 Principles of Burning Man. (I do not know whether there is a connection between Hyde’s work and the growth of Burning Man—it would be interesting to find out.) UPDATE: Indeed, Larry Harvey, founder of Burning Man, got the term from Hyde.