Continuing our examination of Ronald Grimes’s mapping of rituals, from the second chapter of his Beginnings in ritual studies.

: Ritual objects :

What, and how many, objects are associated with the rite? … Of what materials are they made? … What is done with it? … What skills were involved in its making?

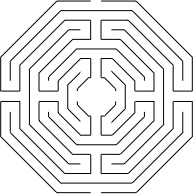

This is an interesting aspect of 3 Old Men for me, since one of the aims in designing this ritual was to make it as simple as possible. You may recall that my original idea involved three old guys in loincloths with staffs: next to nothing to transport or keep up with. The addition of the labyrinth added a lot more cost and transportation issues, but our ritual objects are essentially the same: skirts and staffs.

Are the skirts ritual objects? Skimming ahead in the chapter, I note that costume is an element of ritual identity.

So that leaves our staffs. They too are part of the identity of the 3 Old Men, since they are part of the archetype of the Elder, our reclaimed masculine version of the Crone, but I think they are more than that. I’m sure everyone remembers Gandalf’s claim at the doors of Meduseld that his staff was just an old man’s prop. Just so: our staffs are our support, but like Gandalf’s staff they embody/symbolize our power as Elders.

The question of how they will be used is still to be determined. I know that when we proceed around the labyrinth, I envision our staffs marking time as we move in unison. It is probable that we will incorporate some kind of ritual/dance movement into our peripatesis using the staffs. The agon involving the offer of struggle: will it involve the staff? If not, then the laying by of the staff becomes ritualistic.

There is one more use of the staffs for which I’ve already planned: whatever other decoration there may be on them—and we haven’t decided even what they will be made of—there will be markings on them which will guide us in the actual laying out of the labyrinth. That means there will be four staffs, not just three: laying them out in a square will give us the corners of the innermost octagon. There is also a centerpoint and the width of the path marked to help lay out the positions of the stakes. Sacred geometry, folks.

There are other objects that keep floating into the plan but which I keep rejecting. I would love to add small stands at each entrance, beside which the Old Men would stand, each with one of the four elements: a bowl of water, a bowl of earth, a brazier of fire, a bell or smudge stick (for air). Participants could use those as they see fit, either before entering or upon their exit. The problem with the stands is severalfold: transportation issues, of course, and stabilization issues. The winds are fierce on the Playa; everything has to be staked and tied down, and there is—as I understand it—a prohibition on campfires, tiki torches, etc., so the brazier would be problematic. Perhaps if the 3 Old Men have a longer life with the regional Burns, the stands can make an appearance.

: Ritual time :

At what time of day does the ritual occur—night, dawn, dusk, midday? What other concurrent activities happen that might supplement or compete with it? … At what season? Does it always happen at this time? Is it a one-time affair or a recurring one? … How does ritual time coincide or conflict with ordinary times, for instance work time or sleeping time? … What is the duration of the rite? Does it have phases, interludes, or breaks? How long is necessary to prepare for it? … What elements are repeated within the duration of the rite? Does the rite taper off or end abruptly? … What role does age play in the content and officiating of the rite?

Again we are dealing with two overlapping rituals, the Grand Ritual of Burning Man itself and the inner ritual of 3 Old Men. Naturally, the grand ritual takes place at the same time every year, with its separate questions of preparation, etc. Interestingly, you might think that the grand ritual of the Festival ends abruptly: burn the Man and go home, but it is not nearly that clear cut. These days the Man burns on Saturday night. Many people then leave on Sunday, but many also stay for the burning of the Temple on Sunday night, which has become an equally important part of the grand ritual. (That is our plan.) And when you think about it, even those singular high points in the grand ritual don’t have a clear ending: thousands gather for what is essentially a big bonfire. Who decides when a bonfire is over?

For the 3 Old Men, these questions have not been answered. In fact, despite Grimes’s warning that his proposed map is not to be taken as a checklist, I think that they provide us a useful guide in deciding how to complete our plans for the labyrinth. Will this be a daily event? At what time of day will we take up our positions as officiants? (Conversations with veteran Burners suggest that dusk is our best bet.) How long will we remain stationed? How will we decide when it is time for peripatesis? How will we decide when it’s time to stop? If we are able to add to our troupe so that we have back-up Old Men—which I think would be awesome—how do we effect the ‘changing of the guard’?

Even the question of the age of the officiants is not firmly answered: at least one of our hopeful participants, i.e., needs a ticket, is not an old man at all and in fact will probably be quite disgustingly fit by the time August rolls around. Can a 30-something don the skirt and staff? A question of ritual identity we will need to examine.

Tomorrow: ritual identity